The Battle of Glenn Máma, Dublin and the high-kingship of Ireland: a millennial commemoration by Ailbhe MacShamhráin.

- Published in Medieval Dublin, edited by Sean Duffy (pages 53-64).

The battle of Glenn Máma (coordinates 53°16′25″N 6°32′57″W) and the sack of Dublin which followed, taking place over the year 999-1000, has been accorded relatively little focus, in comparison with Clontarf, by historians of the later Viking Age in Ireland and Scandinavia. The importance of Clontarf has been appreciated at least since the twelfth century, that particular conflict is at once the highpoint and tragic finale of the Ua Briain propaganda work Cogadh Gaedhel re Gallaib (the War of the Irish with the Foreigners), which purports to chart the rise of the Dál Cais, the reign of Brian Boróma and his death in the struggle against the heathen. Clontarf is almost as prominent in Scandinavian saga. It forms an important part of Njal’s Saga and presumably featured in the now lost Brian’s Saga (Bugge 1908, 55, 59-66; Magnusson & Paulsson 1960 341; Ó Corráin 1998 447-452). Quite aside from its survival in popular tradition, Clontarf attracted the attention of medievalists in the earlier decades of the twentieth century, including Goedheer (1938) and Ryan (1938); it continues to be used as a marker by present-day historians (for example Ó Cróinín 1995, 272), and justifiably so, if only because the removal of Brian opened up opportunities for other dynasties. However, scholars appear to have been slower to recognize the importance, in its own right, of the Battle of Glenn Máma, and it has attracted rather little discussion. In more recent decades, several commentators have indeed acknowledged that the battle (fought within a days march of Dublin) represented a turning point in Brian’s career, Ryan (1967, 361) and (Ó Corráin (1972, 123). have both viewed the battle as a key stage in the conflict between Brian and Máel Sechnaill, a victory which gave him the confidence to challenge the Uí Néill king of Tara for supremacy in Ireland.

Such attention, therefore, as has been accorded to Glenn Máma concerns its place in that context for ascendancy which many, contemporary commentators and historians alike, have viewed as a struggle for the high kingship of Ireland. While accepting the importance of its place in this broader picture, it seems appropriate here to view the engagement more in the context of its Dublin dimension. There are indications, as is argued below, that Brian had designs on Dublin for some years prior to Glenn Máma as, indeed, had his rival Máel Sechnaill. The question of Brian’s responsibility for exacerbating the unrest which led to Glenn Máma – perhaps through misreading the complex political relationship between the Hiberno-Scandinavian kingdom and the north Leinster dynasty of Uí Dúnlainge – and the extent to which he may have appreciated the importance of Dublin in the context of Irish Sea politics, are among the other issues addressed.

The career of Brian has been widely discussed, and the stages by which he rose to challenge for supremacy in Ireland are charted in several surveys (Ó Corráin 1972, 120-131; Duffy 1997, 31-6). For present purposes, a brief synopsis will suffice. Without doubt, he exercised considerable political power; ultimately, he did force submissions from each of the other provincial kings and from the Norse of Dublin, displacing (and arguably exceeding) the ascendancy long claimed by the Uí Néill kings of Tara and achieving, as has been claimed, a special status. On he occasion of his visit to Armagh in 1005 when, as is recorded in the Annals of Ulster, he deposited the sum of twenty ounces of gold on St Patrick’s altar, a not in the Book of Armagh (albeit entered by a partisan) style him Imperator Scotorum of Emperor of the Irish (Gwynn 1978-9; Duffy 1997, 33-4). However, it seems unlikely that, from the commencement of his reign, he possesses a blueprint for achieving this supremacy. Nor was it the case that he had come from nowhere to challenge for political dominance in Ireland, despite the claims of Cogadh Gaedhel re Gallaib, whose authors wished to dramatise his rise to power. For his very accession to kingship, much less by the time of Glenn Máma, his dynasty of Dál Cais was well placed at regional level. As shown more than thirty years ago by Kelleher (1967 230-41), it is certainly the case that Brian’s inheritance from his father and brothers – if it did not quite amount to mastery of Munster – certainly provided him with a firm basis from which to establish overkingship of the province.

The possibility should perhaps not be discounted that Brian’s father, Cennétig son of Lorcán, did benefit politically from a strategic marriage with the still powerful Clann Cholmáin dynasty of Uí Néill, as long as the importance of this connection is not overestimated (Kelleher 1967, 230-1, cf Ó Corráin, 114-5). It happens that Cennétig’s daughter Orlaith was married, while apparently still in her teens, to the ageing king of Tara, Donnchad son of Flann. In 941, Donnchad captured the Eoganachta king of Cashel, Cellachán, which probably did help the Dál Cais cause, whether or not that was the intention. That same year, however, the year in which Brian was born according to a retrospective entry in the Annals of Ulster, the king of Tara had his young wife executed for adultery; his apparent willingness to do so might indeed suggest a marriage of convenience with a lesser dynasty, the continued support of which was not crucial for him. It may merely be coincidental, then the death of Donnchad in 944 was quickly followed by a reassertion of authority on the part of Cellachán of Cashel, involving a battle which cost the lives of two of Cennétig’s sons.

The question of Uí Néill support aside, however, other circumstances can be discerned which almost certainly facilitated Dál Cais expansion in the early to mid tenth century; not least among those is political fragmentation within the Eoganachta dynasties, and the potential which existed to exploit a conglomeration of minor ruling lineages in the lower Shannon basin. The fact remains that Cellachán, at his death in 951, is styled Rí Tuathmuman (king of Northern Munster) in the annals of Innisfallen, and Rígdamna Caisil (one eligible for the king of Cashel) in the Annals of Ulster. Although his son and successor Lachta, slain in an internal conflict in 853, is not accorded a similar accolade in his obit, he may nonetheless have advanced the cause of the Dál Cais. His short reign saw an attack against Clonmacnois which involved the Munstermen supported by foreigners, presumably Hiberno-Scandinavians. Later his brother Mathgamain defeated and subjugated the Norsemen of Limerick and managed to overawe some of the Eoganachta dynasties, but clearly not the Eoganachta of Raithlenn under Máel-muad son of Bran, whose base kingdom lay in Co Cork and who remained powerful in south Munster. Although Mathgamain did not achieve effective control over the province but was captured put to death by Máel-muad in 976, it may be noted that the annals style him king of Cashel at his death.

The immediate priority for Brian, nonetheless, was to re-establish the position of his dynasty in Munster, a task which took several years. The annals relate how he suppressed the Norsemen of Limerick, Uí Fidgenti (a kingdom in west Co Limerick), and the Eoganachta of Raithlenn – defeating and slaying Máel-muad at Belach Lechta. By 982, he was ready to move against the Nore Valley kingdom of Osraige, in effect a buffer-state between Munster and Leinster. This was apparently a cause of concern for the Clann Cholmáin king of Tara. Máel Sechnaill son of Domnall, who only two years earlier had severely defeated the Norse of Dublin at the important Battle of Tara. It required no great imagination to see a foray into Osraige by a Munster overking as a step towards asserting authority over Leth Moga (the southern half of Ireland); this at any rate would mean Munster lordship over Leinster – whether or not it was extended to include Dublin. Opting for a pre-emptive strike, Máel Sechnaill attacked the heartland of Dál Cais (in east Co Clare) and leveled the Tree of Mág n-Adair, which had once been held sacred by the ancestors of Dál Cais and had retained a special significance. Undeterred by such calculated insults Brian, in 983, directed his forces up the Shannon against Connacht, over which Máel Sechnaill claimed sway. The same year, he again harried Osraige, taking hostages. This time he did, as Clann Cholmáin had feared, continue into Mág nAilbe (a plain in Co Carlow) and took hostages from the Leinster dynasty of Uí Dunlainge.

It seems that Brian, by this time, had designs on Dublin, he had witnessed the heavy defeat inflicted on the Norsemen by Máel Sechnaill, and perhaps anticipated that his rival might move to dominate the town. In 984, he formed an alliance with sons of Harald, after they brought a fleet to Waterford. There were representatives of the Limerick dynasty, which his brother Mathgamain had earlier banished and, understandably, might have welcomed an opportunity to establish themselves in a new kingship. For Brian, the prospect of dominating a wealthy east-coast trading centre through compliant sub-kings was, presumably, attractive as an end in itself; however, it is possible that, mindful of the close Hebridean connections of his new allies, he already realised the potential of Dublin as a key to the Irish Sea. In any event, Dál Cais and the Limerick Norsemen planned a joint initiative. According to the Annals of Inisfallen, the two sides exchanged hostages and mutual guarantees, in preparation for an expedition against Dublin. A campaign was launched against Osraige and Leinster, and might have proceeded further but for a revolt of the Deisi, a sub-kingdom in eastern Munster (mainly in modern Co Waterford), which destabilised the province to a considerable degree. It took Brian at least two years to re-establish control. He harried the lands of the Deisi, bringing them to heel, but in 986 found it necessary to imprison his nephew, Aed son of Mathgamain, and the following year led a hosting across Desmumu (south Munster), taking hostages at Lismore, Cork and Emly. These campaigns occupied his attention during the interval in which his initiative against Leinster and Dublin had lost its momentum.

The late 980s and early 990s witnesses a renewal of the contest between Brian and Máel Sechnaill; the Munstermen campaigned up the Shannon waterway, striking not only at Connacht but now at the Westmeath lakelands. Their achievement, in military terms, could at best be described by the Connachts, while on another they reached beyond Lough Ree and into the land of Breifne. Gradually, they wore down the resolve of Máel Sechnaill. The latter had certainly been active; in 989, he had subjugated Dublin taking hostages and tribute, and then carried the war southwards. In 990 he defeated the Munster men at Carn Fordroma and in 993, according to the Four Masters, he sacked Nenagh. The very fact that Brian appeared so resilient in the face of these setbacks may have caused Máel Sechnaill to become discouraged,. The indications are that Brian was still determined to extend his lordship over Leth Moga and, conscious no doubt of his rival’s assertion of lordship over Dublin, had not abandoned his ambitions in relation to the Hiberno-Norse kingdom. In the military sphere, Dál Cais proceeded slowly and with caution from 991 onwards. That year, Brian led a hosting against Leinster. In 995, he constructed extensive fortifications around his home province of Munster, before leading another expedition into Leinster in the following year. This time, he marched to Mág nAilbhe (as he had done thirteen years earlier) in Co Carlow and took the hostages of the Uí Chennselaig dynasty and of the west of the province in general.

In parallel with these developments, some diplomatic realignments on Brian’s part may be viewed in the context of his ambitions in relation to Dublin. It seems that he divorced his wife Gormlaith, whose father Murchad (sl 972) of the Uí Faeláin dynasty, had reigned as a nominal overking of Leinster. The separation of Brian and Gormlaith clearly had the potential to complicate political relationships, as her former husbands included Amlaib Cuarán (d981), king of Dublin, and Máel Sechnaill, king of Tara. Her offspring included Sitriuc Silkbeard, king of Dublin (Ó Cronin 1995, 263-4). There was certainly a belief that she used her personal influence against Brian’s interests after she returned to her own kindred. Episodes of Cogadh Gaedhel re Gallaib and Njal’s Saga credit her with inciting her brother Máel-Mórda, and her son Sitriuc Silkbeard, against Brian, prior to the Battle of Clontarf (Magnusson & Palsson 1960, 342, 344); no surviving evidence, however indicates that she played any such role in the lead-up to Glenn Máma.

Meanwhile, in the early 990s, Brian embarked on his third marriage, to Echrad, daughter of Carlus of Uí Aeda Odba, king of Gailenga Becca (Ryan 1967, 365-5). Given the relative unimportance of his new wife’s lineage, the motive for such alliance might at first sight appear obscure. The explanation, however, probably lies in the geography of politics. While branches of the Gailenga were scattered through counties Meath and Westmeath, Gailenga Becca lay in the south of the plain of Brega – well within the Dublin over-kingdom known as Fine Gall (Fingal). It is said that Glasnevin lay in this statelet of Gailenga Becca (Byrne 1968, 393). A difficulty remains, insofar as the ruling lineage of the Uí Aeda was associated with Odba, a site which the nineteenth century scholar O’Donovan located near Navan; however, as the placename merely designates a knoll, it seems reasonable that there was ore than one site of the same name. Some references to Odba suggest a location in southern Bregga, which certainly leaves it possible that the location lay within Fingal. For an ambitious ruler anxious to challenge for overlordship of Dublin, an opportunity to secure a foothold, within the Hiberno-Scandinavian overkingdom would, no doubt, have been welcome.

As the 990s came to a close, Máel Sechnaill, acknowledging his inability to subdue Brian, appears to have decided to ‘cut his losses.’ A rigdál (royal meeting) was arranged in 997 at Clonfert (more precisely at Port da Chaineoc, according to the Annals of Innisfallen), and agreement reached on the partition of Ireland into its ‘traditional divisions’ of Leth Cuinn (the northern half) and Leth Moga. In effect, therefore, suzerainty of the southern half of Ireland was being conceded to Brian by the Uí Néill king of Tara. In certain respects, such a meeting and such a concession was not entirely unprecedented. More than two-and-a-half centuries earlier, overkings of the Uí Néill and of Munster had met at Terryglass to agree spheres of influence along such lines (Ni Chon Uladh 1999, 190-6). On this occasion, however, Dublin was in the equation; Máel Sechnaill gave over to Brian the hostages of Leinster and of the Hiberno-Norse kingdom of Dublin, which he had taken in 989. This particular transfer of lordship would have serious import. In the event, it transpired that the ‘Agreement of Clonfert’ was short-lived, the two kings campaigned together in 998, and took further hostages from the ‘Foreigners’ meaning, it seems, the Norse of Dublin. Brian then took hostages from Connacht and presented them to Máel Sechnaill – a magnanimous gesture intended, to convey, that he was the superior ruler. At this pint, serious unrest broke out in Leinster and Dublin which drew the attention of Brian.

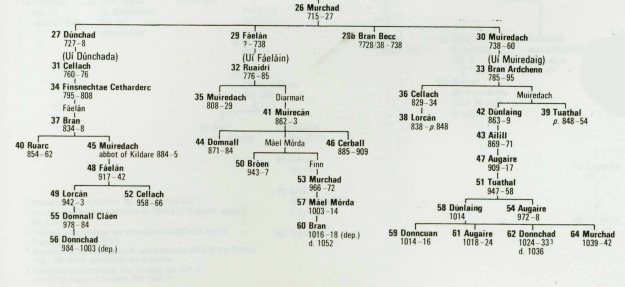

The immediate cause of this unrest may well lie in the relationship between Brian and his new tributary kings. It is probable that Dublin, in particular, having resented the overlordship of the Uí Néill, was even less willing to yield to Dál Cais (Ó Corráin (1972, 123). Furthermore, it appears that Brian, responding to the mounting crisis in 998, fanned the embers of discontent. Ultimately, however, the roots of the problem lay in the dynastic politics of Leinster and Dublin, the complexities of which Brian either failed to comprehend fully or chose to disregard for the sake of expedience. The north Leinster dynasty of Uí Dunlainge had, some two centuries earlier, become divided into rival lineages, two of which – Uí Dunchada, based at Liamain (Newcastle-Lyons, on the Dublin-Kildare border), and Uí Faeláin, based in north Co Kildare – were, in the late tenth century, contesting a nominal overkingship of the Leinstermen. Since the mid 980s, this particular dignity had been held by a member of the Uí Donchada, Donnchad son of Donall, who by this time was subordinate to Brian. Geneaology of the Ui Dunlainge kings of Leinster summarised by FJ Byrne

Geneaology of the Ui Dunlainge kings of Leinster summarised by FJ Byrne

For many year, Uí Dunchada, along with other Irish dynasties adjacent to Dublin, had been severely repressed by the Norse rulers, and remained in their shadow even after Máel Sechnaill had reduced the Norse kingdom’s military might and placed it under tribute. When, in 993, a conflict between the Hiberno-Norse dynasties of Dublin and Waterford (Duffy 1992, 96) caused the temporary expulsion from Dublin of its king, Sitriuc Silkbeard son of Amlaib Cuarán, Uí Dunchada backed the Waterford Norsemen. Presumably the intention was to secure greater support for their own cause from a new regime. Unfortunately for them, they had made the wrong choice and paid the penalty when, a short time later, the Uí Faelán ruler, Máel-mórda son of Murchad, engineered the return of Sitriuc. These two were, of course, related, being uncle and nephew: Máel-mórda’s sister Gormlaith, once the wife of Amlaibh, was Sitriuc Silkbeard’s mother. Acting as allies, Máel-mórda and Sitriuc pursued a vendetta against Uí Dunchada (MacShamhrain 1996 88-89), before the end of 994, they killed Donnchad’s cousin Gilla-céile son of Cerball. Two years later, they slew another of his cousins, Mathgamain, a brother of Gilla-céile. They also killed Ragnaill, a member of the Waterford dynasty. By 998, it seems that the situation had deteriorated further. Late in the year, Brian intervened directly and ravaged Leinster. It is not clear whether this action was intended merely to overawe Leinster and re-state Dál Cais supremacy, or had the more strategic purpose of supporting the Uí Dunchada rulers against is rivals. In any event, it does not appear to have helped matters.

In 999, Donnchad son of Domnall was taken prisoner by Sitriuc Silkbeard of Dublin, again acting in collaboration with Máel-mórda, who assumed overkingship of the Leinstermen. Uncle and nephew then revolted against the overlordship of Brian. Indications are that a delay of a couple of months ensued as the latter, having duly considered his options, mustered his forces. That December, Brian, (styled king of Cashel in the Annals of Ulster) led an army towards Dublin. Regarding the composition of this army, it may be noted that only the Clonmacnois set of annals, which may be seen as pro-Uí Néill, mention Máel Sechnaill in connection with the expedition. The Annals of Innisfallen and Cogadh Gaedhel re Gallaib, both of which may be accused of being (to varying degrees) pro- Dál Cais, are quite explicit in their claim that Brian’s command consisted solely of the “choice troops of Munster.” It may be significant, then, that the generally reliable Annals of Ulster, in its account of Glenn Máma and its sequel, refer only to Brian and indeed imply that he alone profited from subsequent submission. None of the sources state that the army spent Christmas on the march but it might be suggested that it did, for on Thursday the 30 of December it was intercepted, but the combined forces of Norse Dublin and the Leinstermen, at Glenn Máma where a decisive engagement was fought.

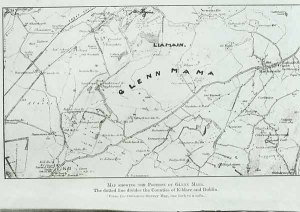

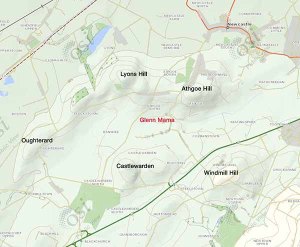

Agreement has been reached on the location of this important battle. The route taken by Brian’s army marching from Munster, clearly a crucial factor in the equation, is of course unknown. The suggestion that he perhaps followed what later became the coach road from Limerick is plausible, but remains unprovable. Nineteenth century scholars, including O’Donovan (1851, II, 739 n z) and Todd (1867, cxlii-iv), were tempted to locate the battle-site in the vicinity of Dunlavin, Co Wicklow. It was later realised that Glenn Máma featured in the itinerary of the tenth-century king of Ailech, Muirchertach ‘na cCochall Croicinn (‘of the leather cloaks) who allegedly make a circuit of Ireland in the winter of 941.

Even, as it now appears, much of the ‘circuit’ reflects the achievement of the later Muirchertach mac Lochlainn (Ó Corráin 2000 238-250), the position of Glenn Máma in the sequence of place names indicates a location not far to the west of Dublin. On this basis Hogan (1910) considered that the site lay in the vicinity of Newcastle Lyons, Co Dublin, and proposed that it be identified with the Glen of Saggart. Given the propensity for battles to take place in border regions (Ó Riain 1974, 68), it seems reasonable to seek a location close to the perimeter of the Hiberno-Norse kingdom of Dublin. On that account, the suggestion of Lloyd (1914, 305ff), which places the battle at a gap now crossed by the Naas Road on the section between Kill and Rathcoole, is still worthy of consideration. In any event, the engagement took place within an easy day’s march of Dublin, as Brian pressed on immediately afterwards to reach the town on the following day.

The sources which offer comment on the scale of the battle indicate that it was no trivial encounter. According to the Annals of Innisfallen, which admittedly tends to represent a Munster perspective, formna Gall herend (‘the best part of the foreigners of Ireland’) fell therein. The more blatantly partisan ‘Cogadh Gaedhel re Gallaib’) bursts into hyperbole (667), claiming that ‘since the Battle of Mág Roth to that time there had not taken place a greater slaughter.” It certainly seems that there was high mortality on both sides. The fallen included Harald son of Amlaib (a brother of Sitriuc Silkbeard) and ‘other nobles of the foreigners’, amongst whom was one Cuilén son of Eitigén, who apparently belonged to the Gailenga; he was perhaps a brother of Ruadacán son of Eitegén, king of Airther Gaileng, who died in 953 (Laski 1997, 134). If so, it appears that Brain’s efforts to secure the support of the Irish dynasties within Fingal had not been entirely successful. As for the casualties on Brian’s side, even the ‘Cogadh’ acknowledges that ‘there fell many multitudes of the Dál Cais, but no details are provided.

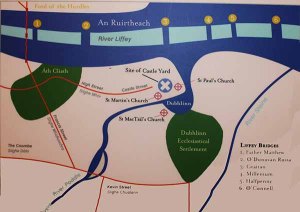

In the immediate aftermath of the battle, Brian’s forces converged to Dublin reaching the town on New Year’s Eve 999. They entered its defences (apparently without any great resistance) and, as the Annals of Innisfallen attest, on New Year’s Day (the Kalends of January) 1000, following an intensive sack, burned both the settlement itself and the nearby wood known as Caill Tomair (it apparently stood on the north side of the Liffey). The plunder of the town, for the second time in ten years, is described in considerable detail in the Cogaidh (s68). Allowance must be made here for poetic license but, event itself, some picture can be obtained of the wealth of the trading centre that was Dublin (Smyth 1979, II 209, 242). According to the account Brian, having plundered the dún (fortress), entered the margadh (market area) and here seized the greatest wealth. Meanwhile, on the approach of the Munster forces, King Sitriuc had fled northward hoping to obtain asylum among the Ulstermen. His ally, Máel-mórda of Uí Faeláin, was captured, in ignominious circumstances according to the Cogadh (s71). At the conclusion of hostilities, the (nominal) overkingship of Leinster was bestowed upon the Uí Dunchada candidate, Dunchad son of Domnail, who retained this dignity until he was deposed in 1003. Brian, however, asserted his overlordship of province by taking hostages from the Leinstermen. Before long, Sitriuc Silkbeard returned having found no asylum in the north. The annal accounts concur that he, too, yielded hostages to Brian while the Annals of Innisfallen add that the latter in a suitable magnanimous gesture, ‘gave the fort (dún) to the Foreigners’; the implications here is that, from this time onwards, the Hiberno-Scandinavian ruler would hold his kingship from his Munster overlord. Apparently Brian, at this stage, aspired to an even tighter dominance of Dublin that than secured by his rival, Máel Sechnaill , ten years earlier.

There seems to be little doubt that the longer term beneficiary of Glenn Máma was Brian alone. With renewed confidence, he again moved against Máel Sechnaill, even if his initiatives of 1000-1001 resulted in setbacks, one expedition into Brega resulted in his advance cavalry being slaughtered by the Uí Néill, another foray was reversed in Míde (Co Westmeath), and the Dál Cais river-fleet was impeded by the King of Tara and his Connachta allies having constructed a barrier across the Shannon. Brian, however, found a way of circumventing it and, early in 1002, brought a large army through to Athlone and took the hostages of Connacht. At this point Máel Sechnaill, finding the support of the northern kings slipping away (Jaski 2000, 227) felt obliged to submit and a new political order was created. The capitulation of the king of Tara left Brian as the most powerful king in Ireland – the first non Uí Néill king to achieve such prominence. However, it lies beyond the scope of this short essay to attempt any evaluation of his recognised success, in breaking the Uí Néill hegemony and making political supremacy appear an achievable goal (Byrne 1973, 267, Charles Edwards 2000, 570), much less to contemplate the realities underlying claims to high Kingship of Ireland.

It remains to consider, though, however briefly the importance of Brian’s victory over the Máel-mórda/Sitriuc coalition as a prelude to renewing the challenge to Máel Sechnaill. Presumably, Glenn Máma gave him a psychological advantage over the king of Tara and increased his readiness to break the Agreement of Clonfert. As a result of the battle, he had achieved domination, in a meaningful sense, of Leinster and Dublin. Perhaps h had some appreciation of the potential of Dublin in accessing the Irish Sea area, certainly, in 1011, he brought a maritime fleet to Cenél Conaill (Co Donegal) – although it is not clear that this included Dublin ships or only those of Limerick. At the very least, he could command the land forces of Sitriuc Silkbeard – and he made us of them in his hostings from 1000 onwards (Duffy 1992, 95). It appears, therefore, that through achieving effective dominance of Dublin, Brian acquired a military (aside from a psychological) advantage over Máel Sechnaill, which helped him in his endeavors to reach beyond the lordship of Leth Moga. His success in this regard was probably instrumental in tying Dublin into the sphere of Leth Moga for at least a century to follow. When the Hiberno-Scandinavian kingdom was eventually, in 1052, brought directly under Irish control, it was by Leinster and subsequently Munster rulers, a pattern which was maintained until 1118. By this time, however, the compilers of Cogadh Gaedhel re Gallaib were already piecing together the orthodox Dál Cais history of the dynasty’s rise to prominence – and Glenn Máma was already part of that past.

References

- S Bugge 1908 Norsk sagafoortuaelling og sagaskrivning I Irland Kristian

- FJ Byrne 1968 Historical note on Cnogba (Knowth), RIA proc, 66C, 383-400

- FJ Byrne 1973 Irish Kings and High Kings London

- T Charles Edwards: 2000 Early Christian Ireland Cambridge

- S Duffy 1992 Irishmen and Islesmen in the Kingdoms of Dublin and Man 1052-1171, Eriu xliii 93-133

- S Duffy 1997 Ireland in the middle ages London & Dublin

- AJ Goedheer 1938 Irish and Norse traditions about the Battle of Clontarf, Harlem

- A Gwynn 1979 Brian in Armagh Seanchas Ard Mhacha ix 35-50

- E Hogan 1910 (ed) Onomiasticon Goedelicum Dublin

- B Jaski 1997 Additional notes on the Annals of Ulster Eriu xiviii, 103-52

- B Jaski 2000 Early Irish Kingship and succession, Dublin

- JV Kelleher 1967 The rise of the Dál Cais, in Rynne E (ed), North Munster studies: papers in honour of Michael Maloney PP 230-41 Limerick

- J Lloyd 1914 The Identification of the Battlefield of Glenn Mama Co Kildare Arch Society Journal, vii 305ff

- S MacAirí 1951 (ed), Annals of Innisfallen Dublin

- S MacAirí and G MacNiocaill 1984 (eds) Annals of Ulster to AD 1131, Dublin

- A MacShamhráin 1996 Church and Polity in pre-Norman Ireland, Maynooth

- M Magnusson & H Palsson 1960 (eds) Njal’s Saga London

- P Uladh Ni Chon 1999 The Rigdál at Terryglass 737AD Tipperary’s Historical Journal 190-67

- Donncha Ó Corráin 1973 Ireland Before the Normans Dublin

- Donncha Ó Corráin 1998 Viking Ireland – afterthoughts, in Clarke HB M Ni Mhaonaigh & R Ó Floinn (eds) Ireland and Scandinavia in the early Viking Age 421-52 Dublin

- Donncha Ó Corráin 2000 Muircheartach MacLochlainn and the Circuit of Ireland in Smyth AP (ed) Seanchas: Studies in early and medieaval Irish archaeology, history and literature in honour of Francis J Byrne 238-50 Dublin

- D Ó Croinín 1995 Early Medieval Ireland 400-1200 London

- J O’Donovan 1851 (ed) Annals of the Kingdom of Ireland by the Four Masters; 7 Vols Dublin

- P Ó Riain 1974 Battle Site and territorial extent in early Ireland, Zestschrift fur Celtische Philologie xxxii, 67-80

- J Ryan 1938 The Battle of Clontarf RSAI Jn lxviii, 1-50

- J Ryan 1967 Brian Boruma King of Ireland in Rynne E (ed) North Munster studies: Papers in Honour of Michael Moloney PP 355-74, Limerick

- Alfred P Smyth 1975-9 Scandinavian York and Dublin, 2 vols Totowa NJ & Dublin